06 February 1981

Meeting Inez Baugh in Shashemene: to be a pioneer is very dread

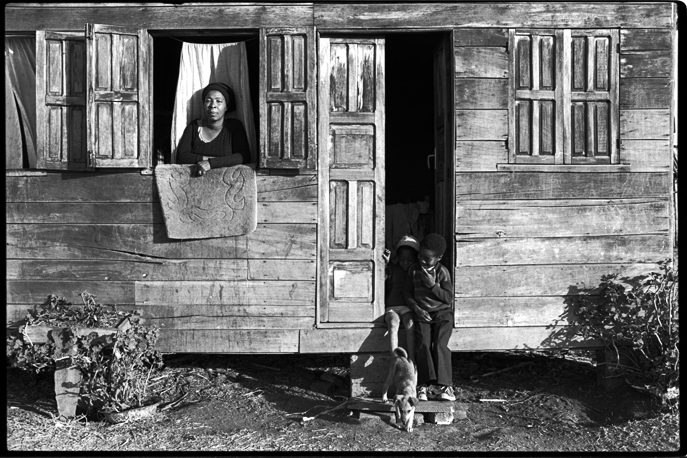

inez baugh looking out from the board house built by her husband clifton after they arrived in shashemene from jamaica in 1968. photo ©derekbishton

DURING my stay in Shashemene I met many remarkable people, none more so than Inez Baugh who told me: “I came here on February 8, 1968 with two daughters and my husband and two months later Haile Selassie came to visit the farm. I have been here 13 years. It’s nice here if you’re a millionaire but for someone who is poor it’s very hard. Sometimes I get very blues. To be a pioneer is very dread.”

Inez had invited me for dinner. Although she and her husband Clifton and their four children lived only a few hundred metres from the compound occupied by the Twelve Tribes, there was very little interaction between them. To be honest, I felt quite guilty that Inez had cooked Jamaican-style cook-up chicken in my honour because that had meant sacrificing one of their precious birds – and it was obvious that the family did not have much in the way of financial reserves.

When Inez arrived in Shashemene with her niece Ann-Marie, who was four months old, and her daughter Jasmin, who was one year four months old, they were full of optimism.

“We were met at the airport by two Jamaicans. I cried all the way down here in the bus. It was an old rickety bus – we left Jamaica on Tuesday and arrived here on Thursday. We just came off the plane and took the bus to Shashemene.” I tried to imagine the sheer strength of will it must have taken to bring two small children from the heart of rural Jamaica to the wide open expanse of the Rift Valley in Ethiopia. “We lived in the town for a month,” Inez said, matter of factly. “Baugh built the house himself.

“When we came here the people didn’t know that you could get two crops a year, but Mr Baugh planted everything – we had corn growing so high that you couldn’t see the road.”

But the early days were not without problems. One day, Inez was attacked by a fellow Jamaican who had come with them to Ethiopia. He cut the little finger off her left hand and her right arm was almost severed completely and even now, many years later, she can hardly move it. She makes light of the problems this disability causes her but I can see the deep sadness if her eyes.

“I don’t have any problems with the Ethiopians because I’m a diplomat. I came before there was any Jamaican embassy here. Mr Shearer, the Jamaica Prime Minister at that time, came to visit us and so did Michael Manley when he was leader of the opposition in 1970.

“After the Prime Minister came and saw the position we were in – fighting with the Pipers, the original Ethiopian World Federation trustees of the Emperor’s land grant to get legal title to a piece of the land – he said he would do what he could to help. Just before the military takeover in 1974 the Jamaican government gave us some money to help build houses. But after the military takeover, all the land was taken away from us and we had no crops at all for a year.

“Andrew, her youngest son, was born the day the radio broadcast that Haile Selassie was dead, August 28, 1975. That was the day that Ivan Coore and Papa Noel Dyer presented a petition to the military government requesting the return of the land that had been seized by local Oromo activists.” That petition was partly successful, in that a porttion of the original land grant was returned to the pioneer settlers.

“Anne-Marie goes to the government school where she doesn’t have to pay, but Dawit (aged 8) and Andrew (aged 5) I have to pay 12 Birr a year, and Jasmin 42 Birr.

“At school they speak Amharic. Their teachers say they speak it better than the locals, who speak Galla. The locals – who are mostly from the Oromo, meaning ‘free men’ group – are against the Amharas. At school they are being taught a lot about communism and although I think they should know about it, it’s a bit too much.

“Sometimes I think about leaving, mainly so that the children can get a better education. The local people are very jealous of us. But my biggest problem is my hand. No one seems to remember us here. But really it’s nice to be in Africa.

“When we came here we were told that it would only be a little while before we got piped water and that the pipes were just down the road. But the minister responsible took them away for his farm and we’re still waiting. If it wasn’t for the revolution we would have gone forward.

“The bakery in Shashemene was run by an Italian and you could buy bread at any time but now you can’t get anything. But look at how much wheat you see at the state farm (where her husband Clifton works). If you could see the amount of hardware that has passed along this road and now the rate at which things have gone up in price. Candles used to be 5 cents: now they are 25 cents. Farenji – even after all these years, people still call me a foreigner.

“I don’t want to go back to Jamaica because it’s not too grand either. I really miss Mr Manley I admire him very much but people don’t want his type.”

“It’s nice here if you’re a millionaire but for someone who is poor it’s very hard. Sometimes I get very blues. To be a pioneer is very dread.”

Inez tells me that Mrs Hillman, the wife of Willy Hillman, a Baptist preacher who came fro the United States to live in Ethiopia and is now their neighbour, went to Montego Bay for a holiday and sent her a postcard saying ‘I can’t understand why you left this beautiful country to come and suffer in Ethiopia’.

“We have a saying ‘I’m in the right church but the wrong pew’,” Inez tells me.

Postscript: When I returned to Birmingham following this trip, I attended a series of talks and reasoning sessions with various Rasta groups. One particularly fruitful meeting was with the Ethiopian World Federation Local 111, which at that time was based in Small Heath, Birmingham. This group first raised funds to send several shipments of dry goods such as rice plus all kinds of tools, household items and so on to EWF members in Shashemene. Subsequently they sent a delegation to Shashemene and helped construct a substantial brick house next to the wooden house that Clifton and Inez Baugh had constructed in 1968. When Inez and Clifton passed, the house was left to their sole surviving son Dawit, who now works in banking in Addis Ababa. He rents the house to a charity called Yawenta Children’s Centre which was launched in 2008 by Sister Isheba Tafari, an Austrian Rastafarian who lived in Shashemene for nearly two decades. Now under the leadership of Sister Bérénice Morizeau, the centre provides free medical, nutritional, psychosocial and educational support to 105 orphans and/or vulnerable children, the majority of whom have HIV/AIDS. The board house than once was the Baugh family’s home is now a classroom while the concrete house built with the help of the Birmingham Rastafari community serves as the main building for most of the centre’s activities. Sister Bérénice wrote to me in 2015 saying: “Visitors regularly pass through our project and I would like to prepare a small exhibition depicting the story and evolution of this place in Amharic, English and French. For that purpose, I believe that your pictures of 1981 are the most appropriate ones I could have to show both our children, staff and visitors how it looked like more than 30 years ago.” I sent her 20 prints which are now on permanent display at the Centre.