4 May 2011

The legacy of Ten.8

#TEN8 #LEGACY

This presentation was originally given by me at a symposium organised by Laura Guy to explore the impact and legacy of the photography magazine Ten.8. It took place on May 4, 2011 at mac, Cannon Hill Park, Birmingham. Other speakers included David Brittain, Manchester Metropolitan University; Dr. Eugenie Shinkle, University of Westminster; and Mark Sealy, Director of Autograph ABP (Association of Black Photographers).

SLIDE 1

Ten.8 was recently described as ‘legendary’. I have to admit, a wry smile passed across my face when I read this – because for many years, Ten.8 wasn’t at all legendary. It attracted lots of other epithets, but never legendary. So I’m particularly grateful to Laura Guy and the mac for organising this symposium, which I hope will help us all to get a better perspective on both the achievements of the magazine, and the extraordinarily creative period in the history of this city that nurtured its growth.

SLIDE 2

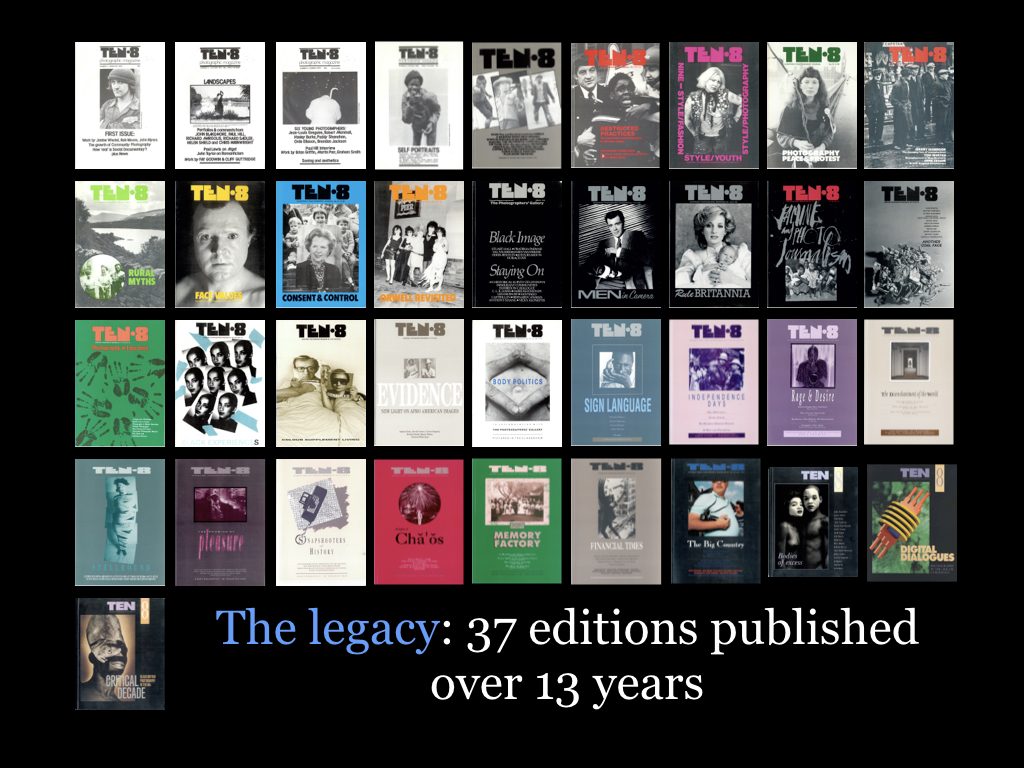

Ten.8 began as a magazine with the stated aim of providing a forum for West Midlands-based photographers to come together and share images and ideas. The first issue was published in February 1979 and had a print run of 500 copies.

Eleven years later, when what turned out to be the last edition, Critical Decade, was published, the local magazine had developed into an internationally acclaimed journal – or Photo Paperback as we rather grandly called it – with distribution across North America, mainland Europe and Australia and more than 1500 subscribers from all over the world. The Digital Dialogues issue sold 5000 copies, and the first print run of Critical Decade – 3000 copies – sold out in months.

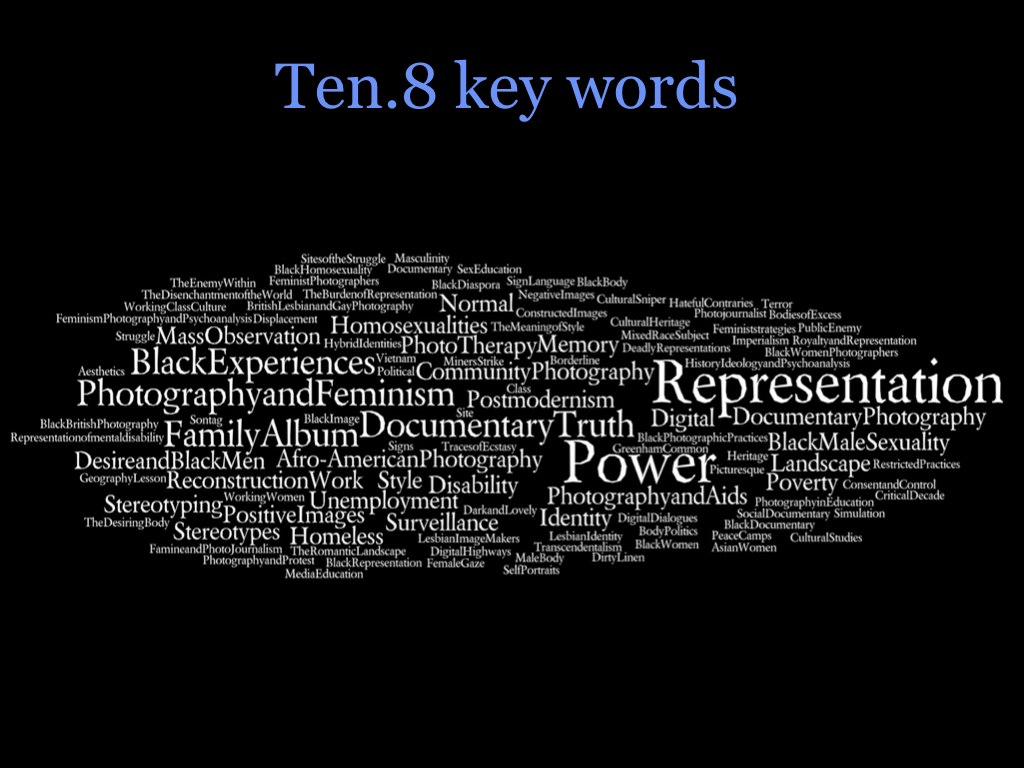

SLIDE 3

In an effort to try to sum up the issues that Ten.8 focused on, I typed all the key words that appeared on the covers and content pages of all the issues and put them into an excellent little bit of free software called Wordle. This program generates a random graphic of the words, with the size of each word related to how frequently it occurs.

I think the obvious conclusion to draw from this is how many words that appear here are not ones that traditionally spring to mind when thinking about photography: and that, as I will attempt to show in this address, is a key element of the Ten.8 legacy.

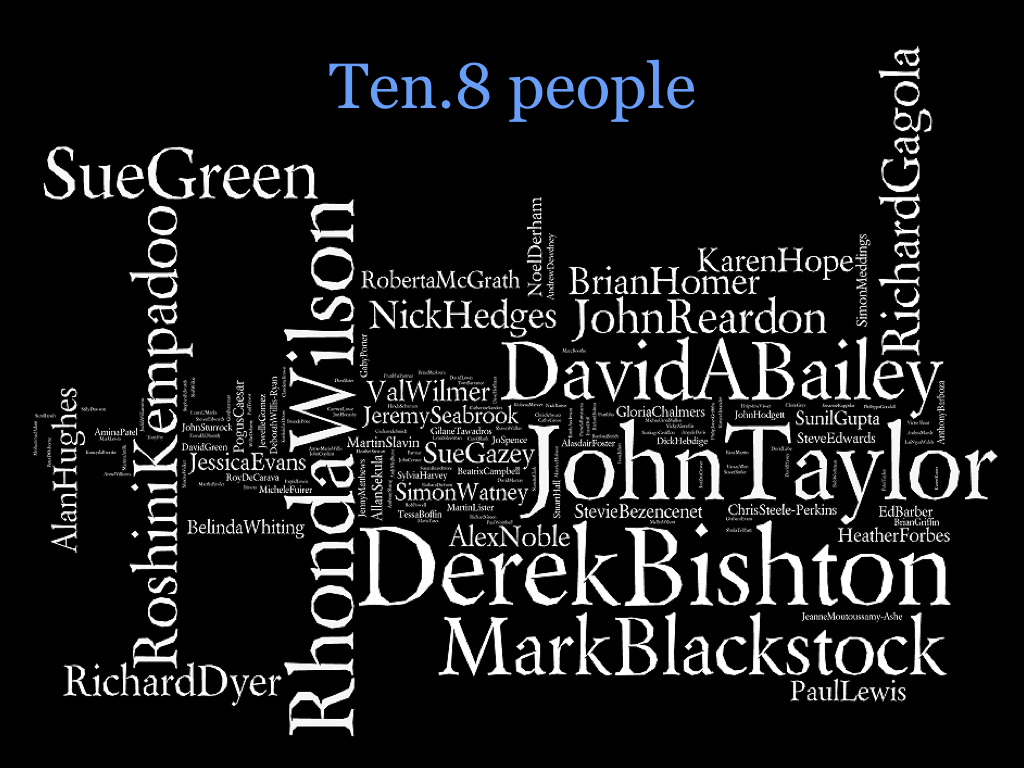

SLIDE 4

I did the same with the names of editors and contributors to create this graphic. Two things struck me immediately when I looked at this map: first, the incredibly strong representation of people from or associated with Birmingham and the West Midlands; and secondly, the vast number of photographers, academics, writers and cultural workers from the UK and beyond who were active in the 1980s and who were attracted to contribute – especially when you consider the pittance they received for their work. But, above all, what this map shows is how Ten.8’s real achievement was to harness some of the most vocal, articulate and diverse voices in the cultural debates of the 80s and early 1990s. Although John Taylor was the most prolific individual editor and was responsible for at least 15 editions – a contribution which I think has never been properly acknowledged and which I hope today’s symposium will go some way to rectifying – 16 other people, including myself, were involved, singly or in tandem with others, in producing the other editions. The triumph of Ten.8 was in bringing together these diverse voices and agendas, allowing the magazine to become an inclusive platform for the ideas and concerns of a generation.

SLIDE 5

What I’m going to try to do today is capture what I think were some of the key moments in the evolution of Ten.8.

First, the ongoing concern about the nature of documentary photography and our assumptions about its validity and usefulness; Second, the role that cultural theory can play in helping us develop new ways of seeing and understanding how images are inscribed with meaning;

Third, the struggles of black image-makers, feminists, and gay and lesbian photographers to put themselves in the frame;

Fourth, the impact of digital technology;

And finally the achievements and legacy of the work Ten.8 undertook in touring exhibitions, opening up international venues for photographers and pioneering the first Birmingham Photography Festival.

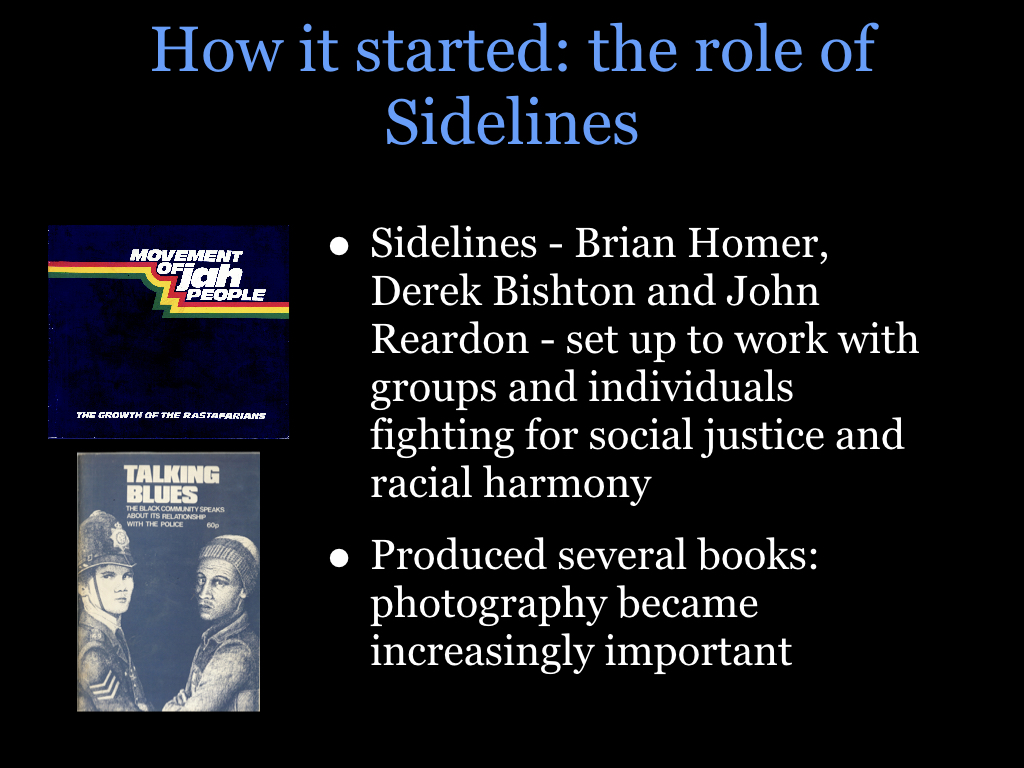

But we’re going to start with its birth in a small upstairs room of a terrace in Grove Lane, Handsworth, courtesy of the Sidelines agency run by Brian Homer, John Reardon and myself.

SLIDE 6

Sidelines was started by Brian Homer and myself as an independent design and publishing agency with the aim of servicing the many organizations, community groups and individuals fighting for social justice and racial harmony in the inner city. We set up our office in a small terrace in Grove Lane.

Handsworth in the late 1970s was a turbulent place. So many issues seemed to be converging. The worldwide economic crisis was devastating traditional Birmingham industries; unemployment, especially amongst the young, was stratospheric; inter generational conflicts were rife; overt racism in the police and other state institutions was a fact of everyday life. Deportations, police beatings, the ravings of the far Right groups like the National Front – all conspired to create the sense of a community under siege.

We produced hundreds of leaflets, booklets, posters, annual reports and so on. Two of the most influential are shown on the screen, Movement of Jah People, the first book published in the UK about the origins and beliefs of the Rastafarian faith, and Talking Blues, which was made up of edited transcripts of black people talking about their interactions with the police, and which was nominated for the Martin Luther King Jnr Peace Prize. We worked with campaigning groups such as Affor, the Asian Resource Centre, to local reggae bands, and community activists. As our client base expanded, photography became a vital part of our work. Neither Brian or I were trained in photography, but when John Reardon – who had studied photography – joined us after a few months, we built a darkroom and started taking it seriously.

SLIDE 7

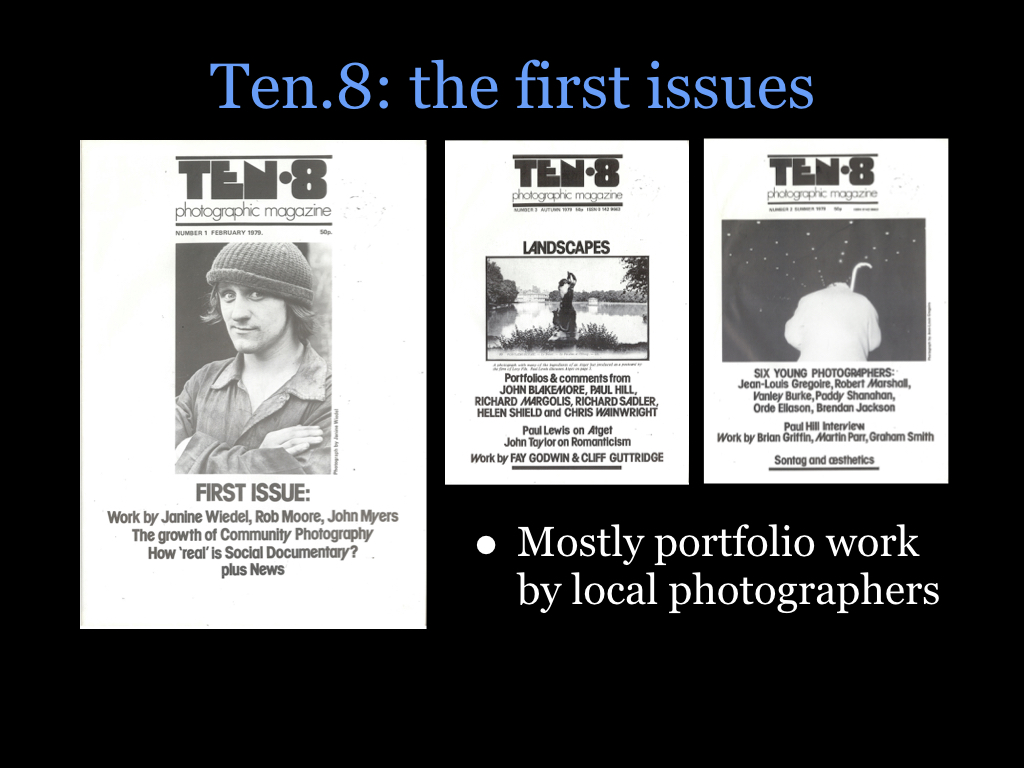

So seriously in fact, that we started agitating for West Midlands Arts to fund a gallery so that we could connect with the many other photographers working in Birmingham at that time. That came to nothing, so we turned to the idea of a magazine. Because of the experience we’d had publishing and creating books and magazines – we’d built a distribution network for Movement of Jah People, and Brian, of course, had for many years been managing editor of Grapevine, Birmingham’s answer to Time Out and knew just about everything there was to know about persuading newsagents and other shops to stock niche publications – we didn’t have much difficulty convincing WMA to cough up a small subsidy for a magazine. That’s when John Taylor and Paul Lewis, who were to become such influential members of the editorial group, joined.

As you can see, the first three issues were very locally based. Janine Wiedel, although based in London, had won a WMA bursary to document the local metal bashing industries, and we featured one of her images on the cover of the first issue. An early indication of our preoccupation with documentary, however, is that article in the first issue ‘How real is social documentary?’ But mostly this was portfolios of work with artist’s statements.

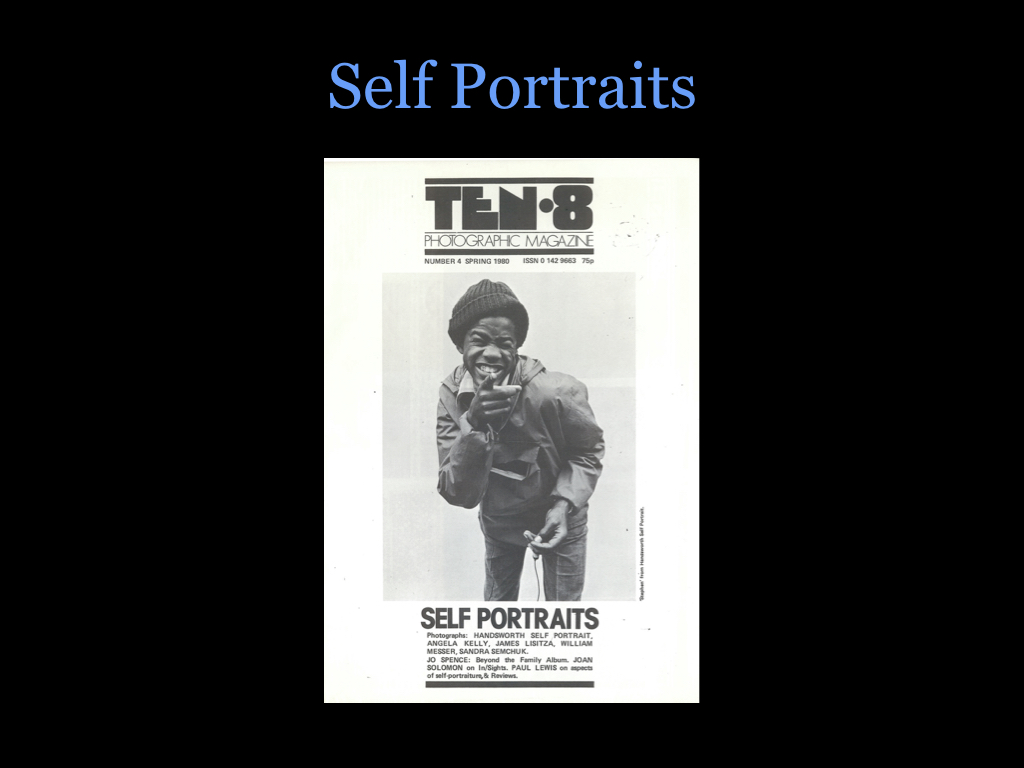

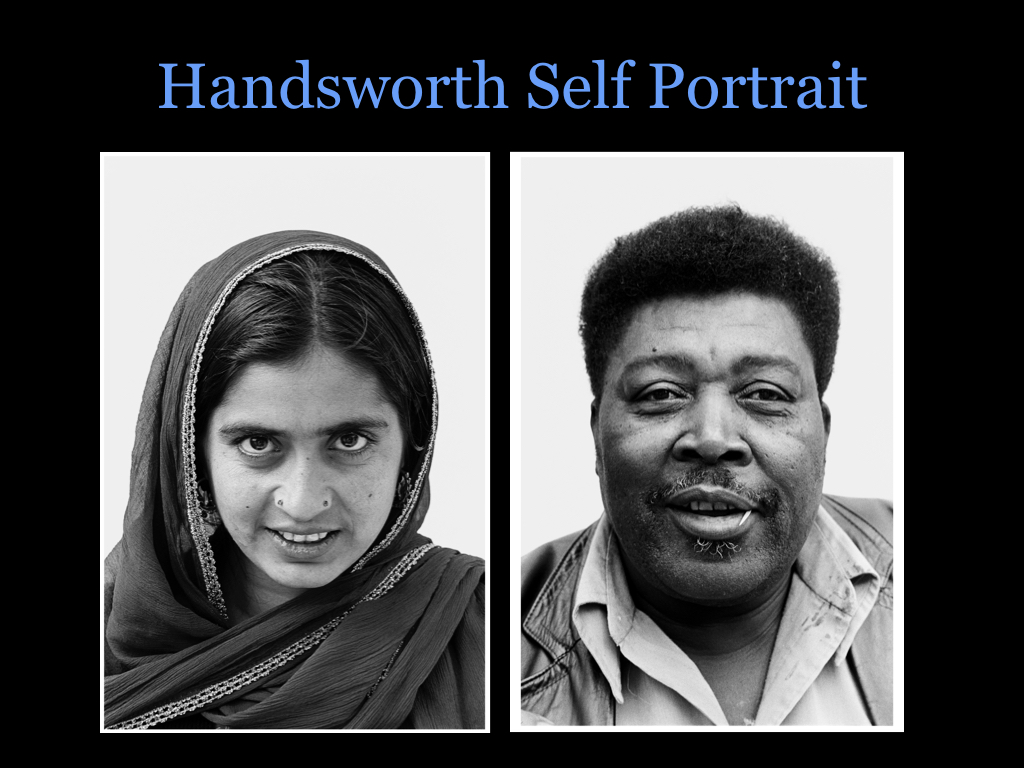

SLIDE 8

All that changed with out fourth publication, the self portrait issue. This was inspired by our own work, the Handsworth Self Portrait project which Brian, John and I had undertaken in the summer of 1979. It was an experiment brought about by the experiences we’d had taking photographs for books such as Movement of Jah People and Talking Blues. One of the most difficult issues we’d had to confront was ‘Why are you white boys photographing black people?’ ‘Are you working for the police?’ was one frequent question. ‘What are you going to do with the pictures?’ was another. All valid questions that we felt we had to address.

SLIDE 9

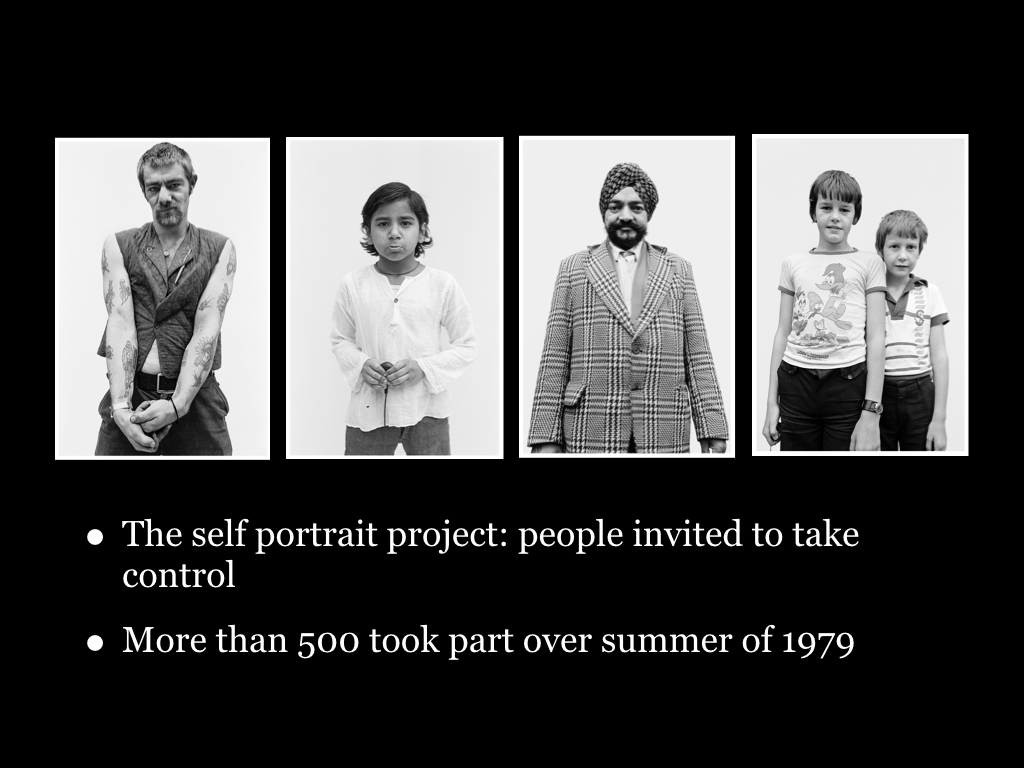

A chance encounter with an issue of Camerawork which had reported on a self portrait session held at an American trade fair in Kiev inspired us. We decided to set up a self portrait booth outside our office in Grove Lane and ask people to take their own portrait in return for a free print.

SLIDE 10

We, the photographers, surrendered control of the decisive moment and the ‘subjects’ took over and presented themselves to the camera in subtly different ways that we had no control over, other than ensuring they were in the frame. We ran six sessions in total. One week we would set up the camera and backdrop. We’d then spend most of the following week processing film – sometimes up to 20 rolls of 35mm film – and making prints, and the following weekend we’d pin them up in the window of the front room and invite participants to collect their free print. As most of them were local and passed by on their shopping trip to Soho Road, we also succeeded in giving away hundreds of prints. More than 500 people took part. It was a very exciting time for us because nearly every single image had something unique about it. It quickly became clear that we were making a documentary of this most diverse, multi ethnic community in an entirely new way.

SLIDE 11

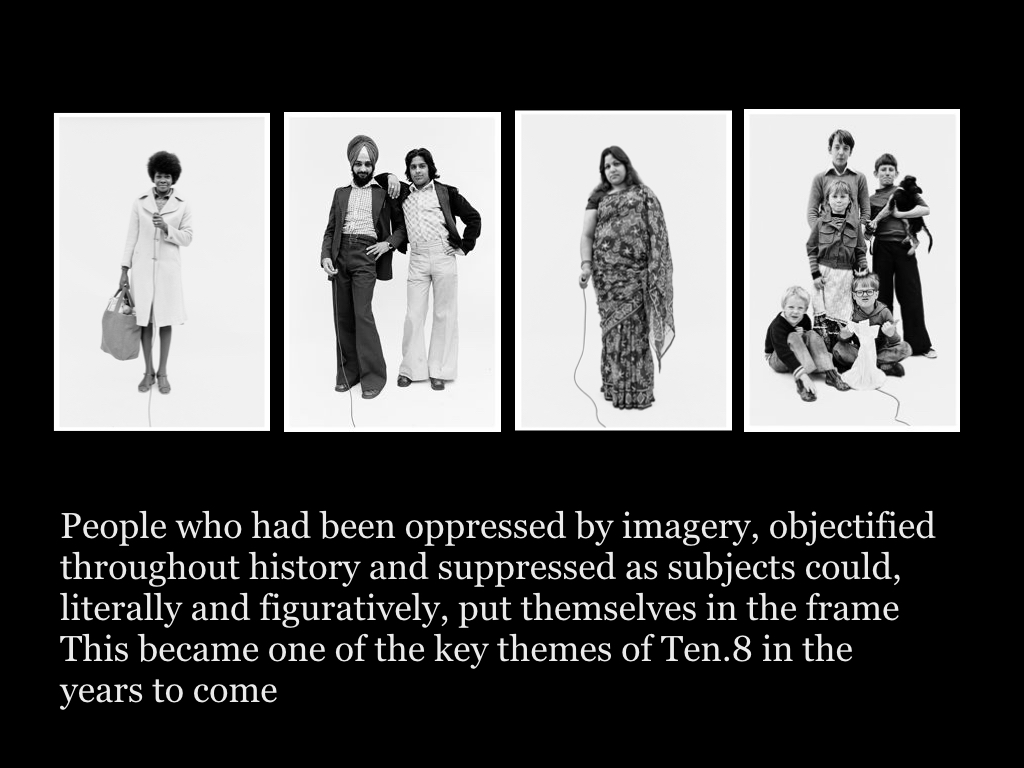

The photographs became deeply influential for all three of us, and made me think more closely about issues of representation and power – and how people who had been oppressed by imagery, objectified throughout history and suppressed as subjects could, literally and figuratively, put themselves in the frame and enter their own subjectivity. This became one of the key themes of Ten.8 in the years to come.

It also marked the end of any idea of a locally focused, portfolio-based magazine. When we decided to publish the self portraits in Ten.8, we deliberately set out to find other examples of self portraiture, and had received submissions from all over the world. In addition, Jo Spence, one of the great innovative voices in independent photography in the 70s and 80s, arrived hot foot from London with an article about her work on the Family Album, which included many self portraits. In the words of the time, Ten.8 had gone ‘outanational’.

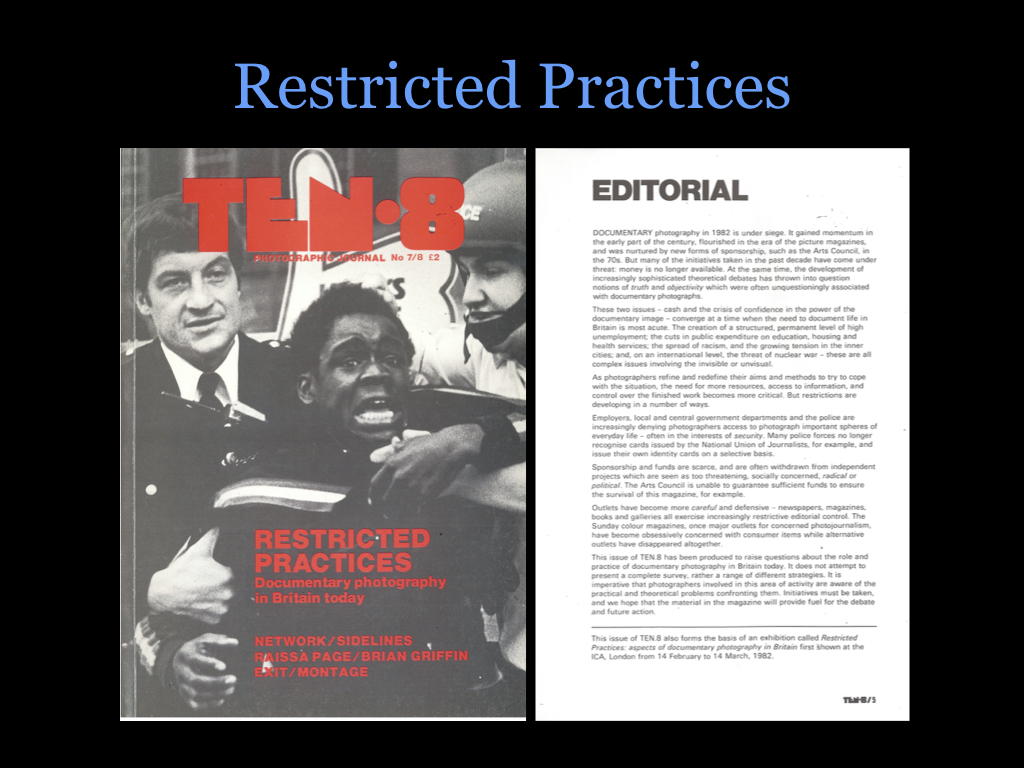

SLIDE 12

Naturally, this caused problems with West Midlands Arts who hadn’t signed up for an international publication. Many months of wrangling and lobbying took place, and eventually, the Arts Council stepped in. The first issue we published under this new regime, in the early part of 1982, returned to theme of the crisis facing documentary photography. The editorial is worth quoting because of the eerie parallels facing arts funding today:

‘Documentary photography in 1982 is under siege. It gained momentum in the early part of the century, flourished in the era of picture magazines … but many of the initiatives taken in the past decade have come under threat: money is no longer available. At the same time, the development of increasingly sophisticated theoretical debates has thrown into question notions of truth and objectivity which were often unquestioningly associated with documentary photographs.

‘These two issues – lack of cash and the crisis of confidence in the power of the documentary image – converge at a time when the need to document life in Britain is most acute. The creation of a structured, permanent high level of unemployment; the cuts in public expenditure on education, housing and health services; the spread of racism, and the growing tension of the inner cities; and on an international level, the threat of nuclear war – these are all complex issues involving the invisible or unvisual.’

SLIDE 13

As traditional outlets for documentary work disappeared – the weekend newspaper colour supplements, for example, which had once been major platforms for concerned photojournalism, became obsessively concerned with consumerism, fashion and celebrity culture, a characteristic that is taken for granted today – so Ten.8 was continually drawn to provide an outlet for work documenting serious issues. Greenham Common and the peace protest, the changing face of unemployment , famine in Africa and the miners’ strike all became the subjects of issues of Ten.8. In issue 11 Jeremy Seabrook argued that one of the reasons photography was struggling to convey the pain of unemployment in the 1980s was that the site of working class struggle had been removed to a less accessible place – the inner landscape of the mind.

SLIDE 14

What was important about these attempts to revalidate documentary was that we never placed the photograph in isolation: they were always, as Stuart Hall said, ‘inscribed into the currency of our discourses’. Looking back over the old issues, I can’t say we always got it right. But this issue on youth subcultures was an example where it worked, I think, because of a quite brilliant piece of writing by Dick Hebdige, which subsequently became a staple on media and cultural studies courses in the UK and beyond.

SLIDE 15

In the same way that Restricted Practices set out an agenda, Consent & Control was another landmark issue in the evolving thinking of the editorial group. The year was 1984, and Orwell’s dystopian vision of the way things might turn out was very much in our minds. But what editor John Taylor set out to demonstrate was that unlike in Orwell’s world where society was controlled by a malevolent group which knowingly manipulated and coerced the ignorant population, in the real 1984 control is internalized: we obey because we agree, because we have bought into ideas of what is normal, what is acceptable, what constitutes being British.

SLIDE 16

John’s editorial introduction said: ‘In this issue we unpack some of the mechanics of power.’ It was the first time we had devoted an entire issue to examining theories of representation, and it was powerful stuff.

Colin Mercer demonstrated, using Gramsci’s theories around hegemony, the role of photographic imagery in generating active consent to an idea of Britain.

John Tagg in The Burden of Representation, explained how, like the state, the camera is never neutral and that representations it produces are highly coded and how the power it wields is never its own.

Roberta McGrath described how, by trading on the belief of documentary reality of photographs, concepts of the normal and abnormal were used to control the poor.

Judith Williamson, taking the debate on from Jo Spence’s earlier work, discussed how the family album is a powerful site of social control

And David Green described how photography has been used to dominate other cultures.

Looking back the other day over this issue from 17 years ago I was struck by its continuing relevance. It was, and remains, a tour de force of how to make complex theoretical concerns accessible and relevant. I can only imagine the glee that greeted it institutions of higher education where media studies were just beginning to get established. It certainly cemented Ten.8’s position as a major player in the much wider field of cultural studies. From this point on, we were no longer just a photography magazine.

Incidentally, this was the last issue produced at the Sidelines office in Grove Lane, which had been subsidising the magazine for six years. Sue Green, who had joined the editorial group around the time of issue 12, had been appointed to run the new Triangle Photography Gallery at Aston Centre for the Arts – so we did get our gallery in the end, although not because of anything Ten.8 had done – and we decamped there. Where our weekly meetings continued in the space above the gallery.

SLIDE 17

For much of 1983 and 84, John Reardon and myself were absorbed in producing a book of essays and photographs about Handsworth, called Home Front. Given some of the work we had been involved in with Ten.8 – questions about racist stereotyping, power and so on – putting together a book of images about a multicultural area like Handsworth was full of pitfalls. I won’t bore you with descriptions of the endless nights we spent arguing and discussing individual images, or sequences of images, but concentrate instead on some of the positives that came out of the experience – one of which was this issue of Ten.8 – Black Image.

SLIDE 18

In the process of sifting through hundreds of our own images for Home Front, I became increasingly interested in the idea that there existed another, alternative photo history of post war black settlement in Britain. This included the formal High Street studio portraits which many of those arriving from the Caribbean and Indian sub continent took to record their arrival in the Mother Country. Although these portraits are powerfully inscribed with the codes of late Edwardian portraiture, they still documented a powerful truth about the lives of the people portrayed – hey, we’ve arrived, we’re getting somewhere, surviving, doing all right. Almost every person arriving from the Caribbean in the 50s and 60s had one of these taken: these two have a great personal significance because the young woman is my wife Merrise and the other her Uncle Waldy.

SLIDE 19

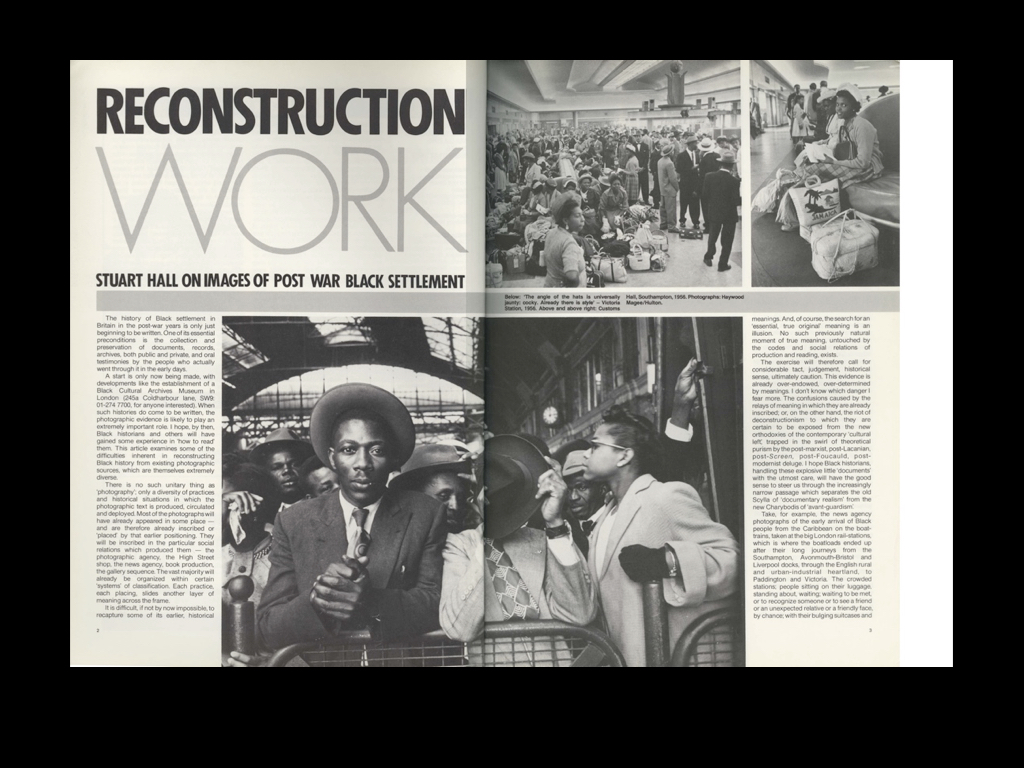

So, in the early part of 1984, I wrote to Professor Staurt Hall and asked him if he would be interested in writing about these photos. He agreed and so began a summer that involved John and myself trawling through the basements of the few High Street photographers that still remained, and in the archives of picture agencies such as Hulton (where most of the images published in Picture Post were then housed), and Keystone to provide him with raw material. The resulting article, Reconstruction Work was probably the most significant single article Ten.8 ever published.

SLIDE 20

I say this for several reasons.

First, it prompted David A Bailey – one of the great cultural networkers and spokespersons of the period – to come to Birmingham to find out more about Ten.8, where he immediately became part of the editorial group.

Second, through David, the magazine came into direct contact with many of the most dynamic voices in black cultural politics in the 80s, such as Sunil Gupta, Iasaac Julien, Kobena Mercer, Sutapa Biswas, Pratibha Parmar, Gilane Tawdros, and Rotimi Fani-Kayode.

This in turn made Ten.8 a key vehicle for mapping what turned out to be a period of rapid and turbulent change in both theory and practice in regard to black image making and black cultural work generally. – namely, the struggle of black people not simply to recover themselves in past histories, but to produce themselves as new subjects for the future. To enter, as Stuart Hall observed, that most modern of all domains, the domain of representations.

I want also to acknowledge the work of photographer and writer Val Wilmer, who apart from contributing several key articles on black photographers such as James VanderZee, also edited Issue 24, Evidence, new light on Afro American images.

SLIDE 21

I have to preface my comments about this issue of Ten.8 with a brief anecdote. My youngest daughter Zak studied Media at Westminster University. About half way through her course, this would be around five or six years ago, she called me and asked: ‘Dad, did you used to edit a magazine called Ten.8?’

Swallowing my disappointment that even members of my own family couldn’t recall what I fondly thought of as one of my significant achievements (although, to be fair, she was only a toddler when Ten.8 folded) I asked: ‘Why?’

‘Well, we’ve just been given an essay topic to look at an edition called Digital Dialogues, and say whether we think it is still relevant to current debates about digital imagery.’

SLIDE 22

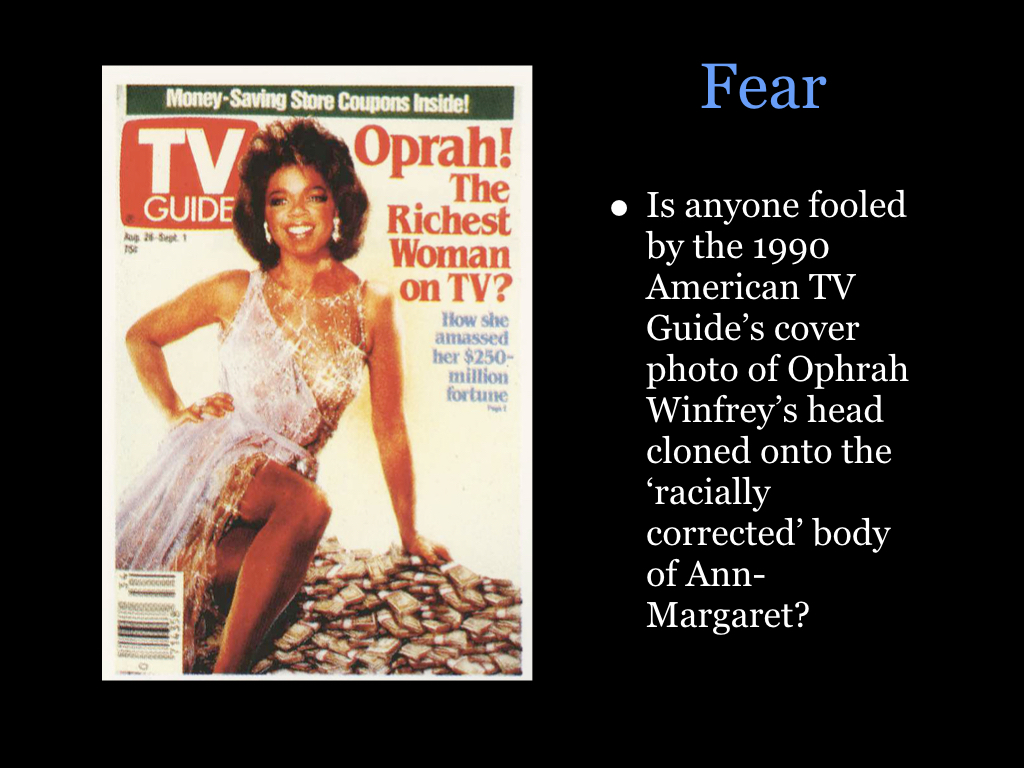

In answer to my daughter’s essay topic, I have to say well yes and no. Fear and Fascination were the keywords of this issue. The fear was that we could be fooled and manipulated more easily. Yet, Twenty years on, when digital technology is all-pervasive, when our phones can take pictures and upload them seamlessly to Instagram or Facebook in seconds, some of the fears voiced in Digital Dialogues sound rather quaint. The furor that surrounded the 1990 American TV Guide’s cover photo of Oprah Winfrey’s head cloned onto the ‘racially corrected’ body of Ann-Margaret looks faintly ridiculous now: we can all see that it’s a fake. The level of our sophistication in terms of reading digital imagery is way beyond what many predicted.

SLIDE 23

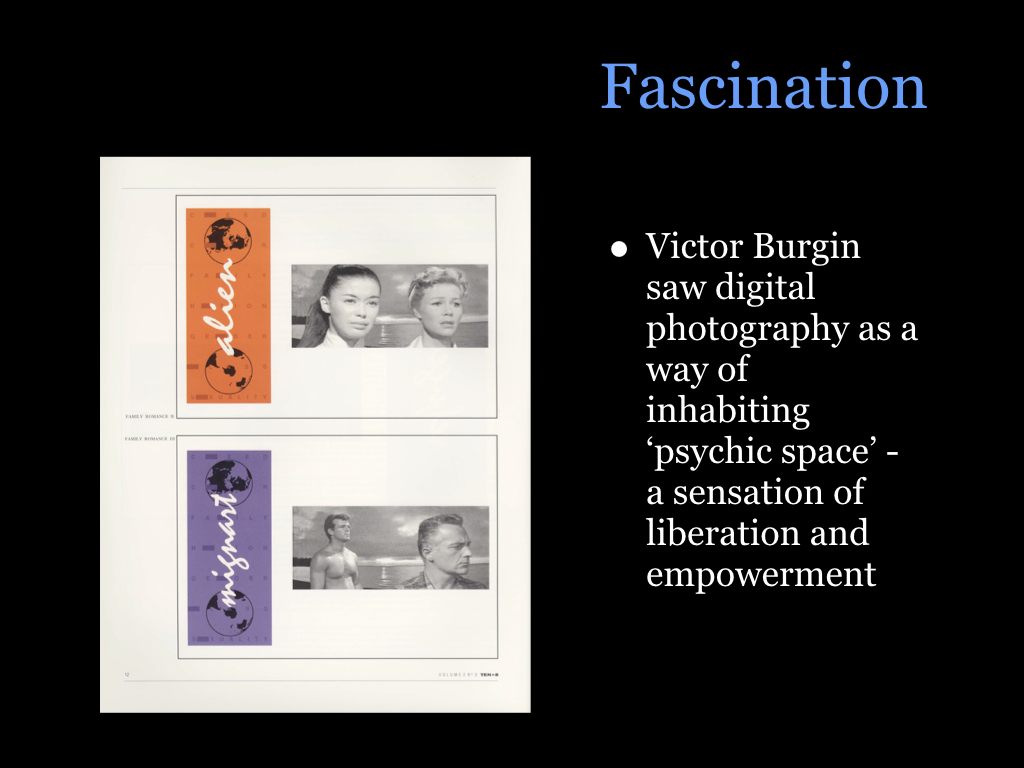

But the understanding of the seduction, the fascination, the dream of a world reduced to information which can be controlled and manipulated with infinite flexibility and creativity was recognized by Victor Burgin in this issue. He said: ‘I see the space of the computer screen – wafer thin and infinitely deep – as an analogue to that of psychical space.’ For him, digital photography was both liberating and empowering.

SLIDE 24

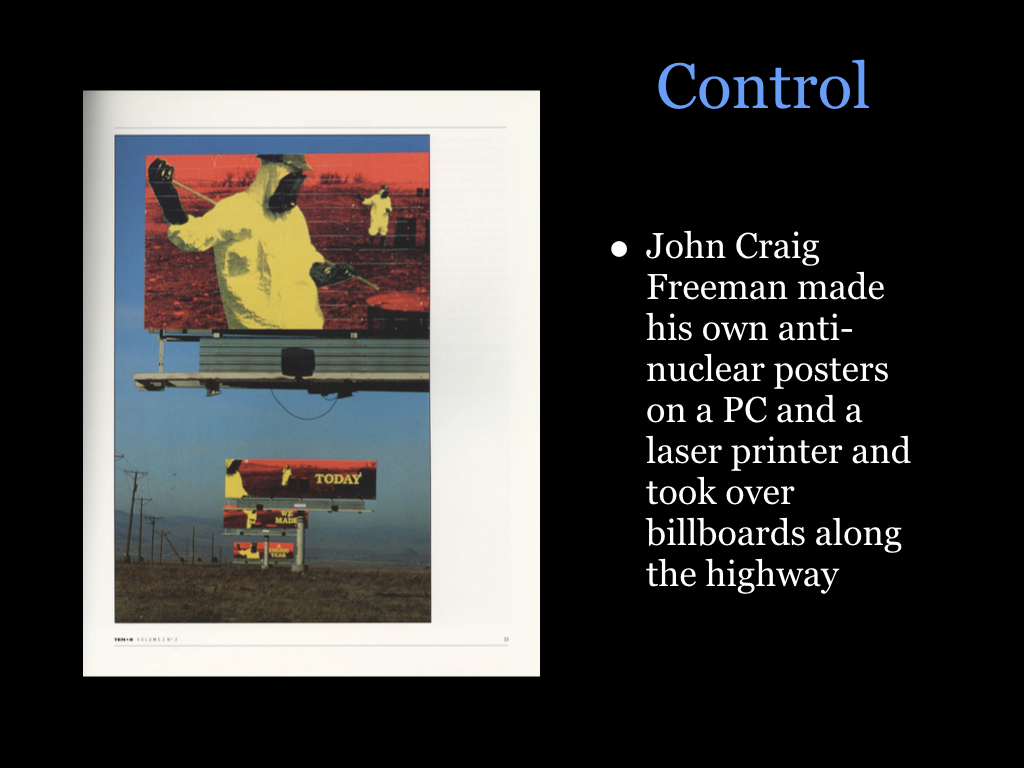

But the project that made the most lasting impression on me, was one by US activist John Craig Freeman. He was part of a group protesting about a nuclear arms facility in Colorado. He managed to secure the use of several giant billboards along the highway near the plant, and using a basic mac computer – we’re talking 20 years ago here, so think about it – an A4 laser printer and a great little program called Postermaker which enabled him to blow up his images by 3200 per cent and print them out s A4 tiles, he made his own giant poster campaign. Even 20 years ago, digital technology made it that easy to appropriate the corporate tools of communication. How prescient was that?

On a personal level, what I took away from this issue of Ten.8 enabled me to work on a range of pioneering digital projects at the Telegraph in the years that followed.

SLIDE 25

I want to conclude by mentioning some of the other activities Ten.8 established, or tried to establish at a local level.

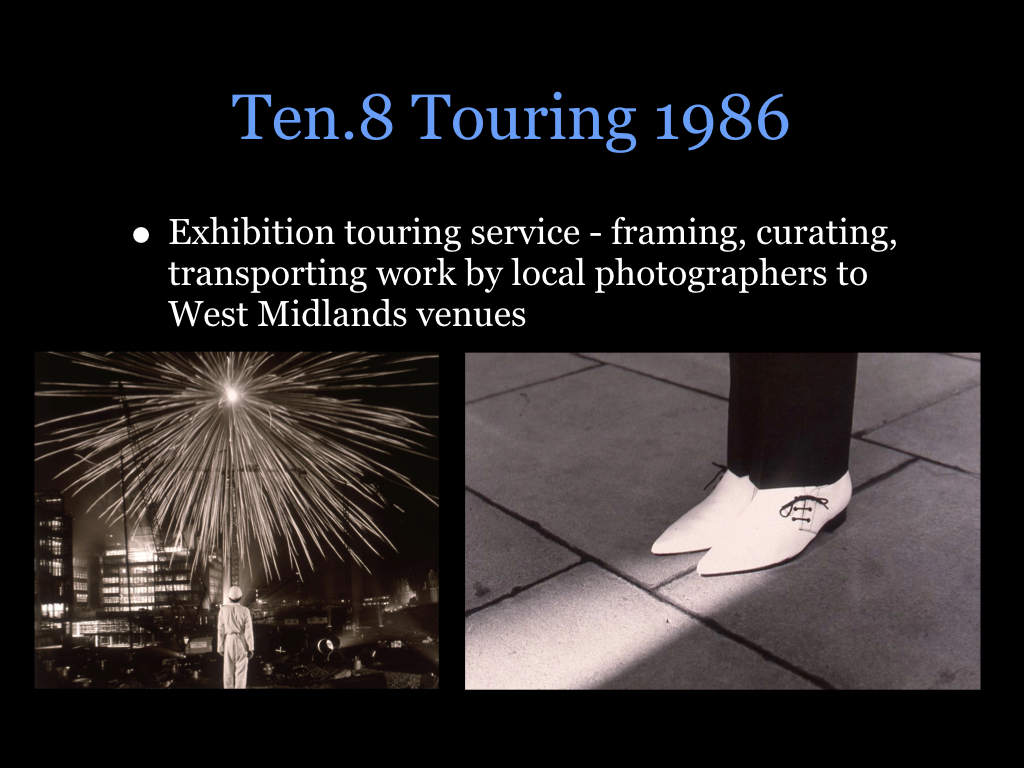

In 1986 West Midland Arts agreed to support a Ten.8 photographic exhibition service which was run for many years by the late and greatly missed Rick Gagola, and then latterly by Rhonda Wilson (now also sadly deceased). The service toured work by Armet Francis, Nick Hedges, Brian Griffin, Roy Peters, Birmingham Photographic Heritage Project – otherwise known as Pete James, Mohammed Riaz, Karem Ram, Marianne Morris, Ming de Nasty, Prem Aujula, Beryl Small, Darryl Georgiou, Rhonda Wilson Jeremy Scales, a group show from Weld and WideAngle, along with a laminated version of Home Front by John Reardon and myself, and the original set of 44 prints that made up the first Handsworth Self Portrait show. In many cases Rick and Rhonda curated the shows, working with the artists to edit and prepare them. The service also archived work by various other photographers from around the region, which now form part of the collection at Birmingham Library. The image shows two photographs by Brian Griffin.

SLIDE 26

In 1990 John Taylor, Rhonda Wilson, Mark Blackstock, David A Bailey and myself were invited to take part in Houston Foto Fest, where we helped curate an exhibition of black British photography which included locally-based people such as Claudette Holmes. We also took part in their portfolio advisory sessions where photographers paid to have 20-minute one-on-one sessions with curators, editors and well-known photographers. In the photo on the right Rhonda Wilson can be seen at one of these advice sessions.

SLIDE 27

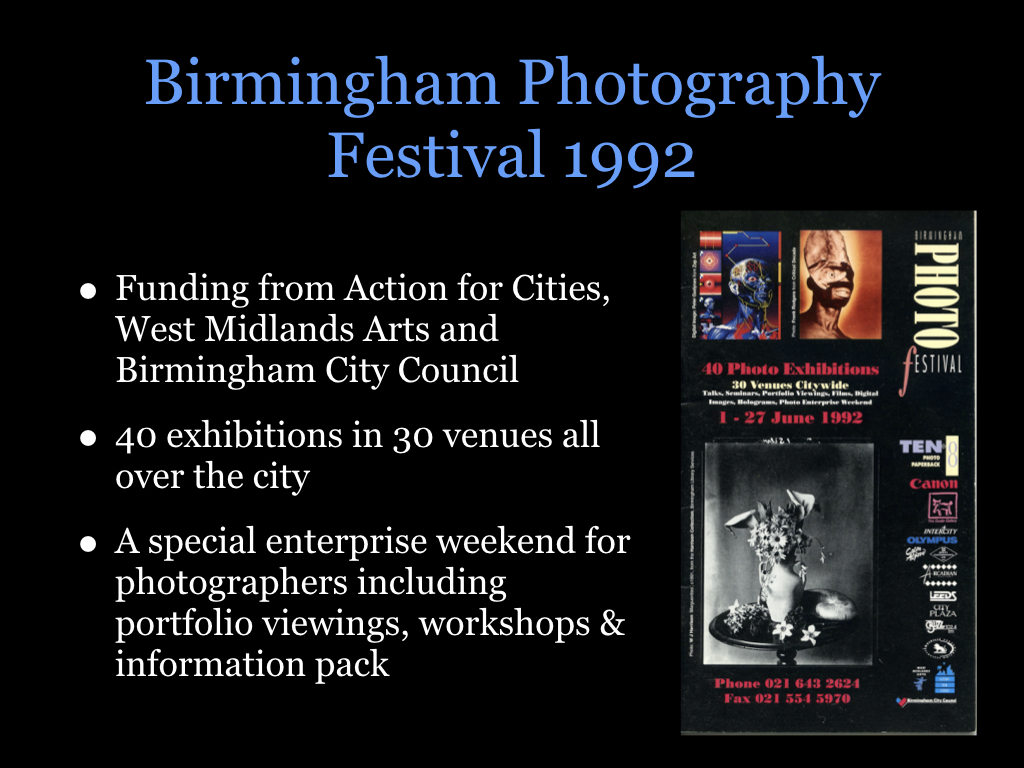

This led directly to a plan to try to establish the same kind of event in Birmingham. In the late 80s and early 90s, Birmingham City Council’s Economic Development Unit toyed with the idea of supporting a media and arts-based cultural and economic renaissance for the city. In July 1990 Ten.8 submitted a feasibility report to the EDU, and although funding for the project never materialized at the level initially promised, the first Birmingham Photo Festival took place the following year at venues around the city, including the old mac.

Rhonda Wilson was one of the main driving forces of this initiative, and the much-acclaimed work she has spearheaded subsequently with Seeing the Light and Rhubard Rhubard had its genesis in this moment.

SLIDE 28

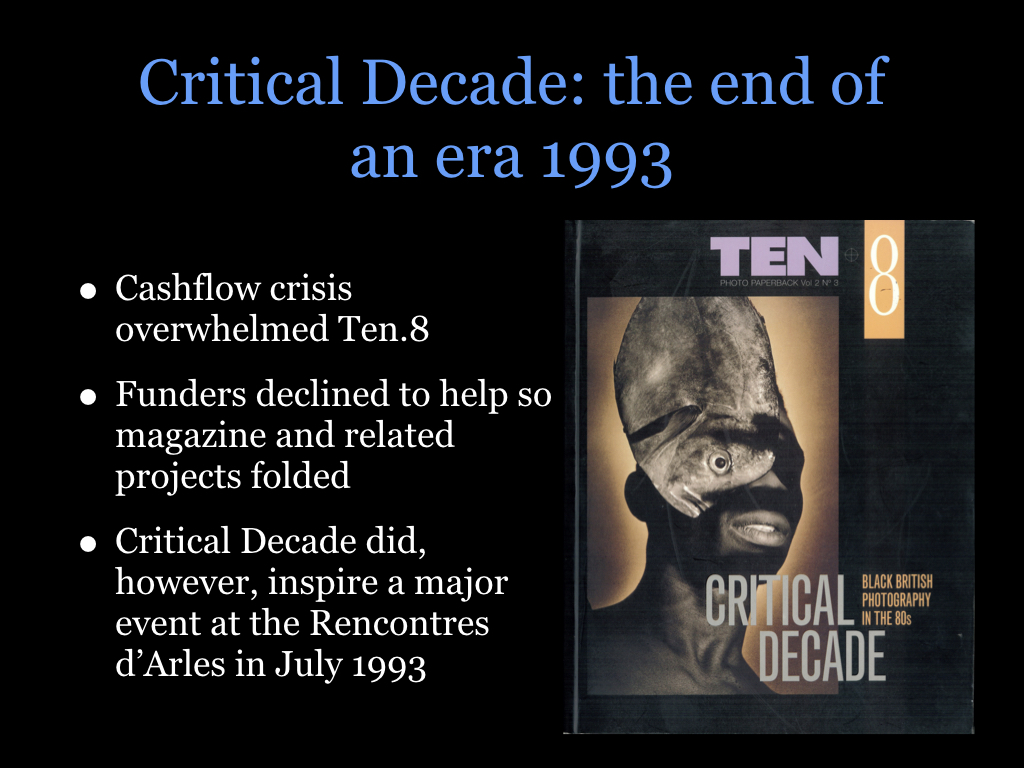

By 1992 Ten.8 was facing a massive cash flow crisis. The economics of periodical publishing are very tough. Cash for upcoming products has to be committed often a year or more in advance, and returns often take years to come in. The economic downturn of the early 90s following Black Tuesday led to astronomical interest rates, and a general reluctance on the part of banks to give overdrafts. Plus ça change. Ten.8 could not raise the capital it needed to carry out its ambitious expansion plans, and it closed, leaving the four remaining directors – myself, Mark Blackstock, David A Bailey and Darryl Georgiou with fairly substantial personal debts.

However, I want to end on a positive note, so I’m going to tell you about the way Mark Sealy from Autograph, armed only with his disarming personality and a copy of Ten.8 Critical Decade persuaded the organizers of the Rencontres D’Arles festival in 1992 to commission an audio visual show of black british photography for the following year.

The Rencontres au Noir presentation in the Theatre Antique, with music by local hero David Hinds from Steel Pulse, was one of the highlights of Arles 1993. Down there in the Camargue they still talk about it. Legacies don’t come any better than that.

Thank you