27 December 1831

Rev Hope Masterton Waddell’s report on the Christmas Rebellion

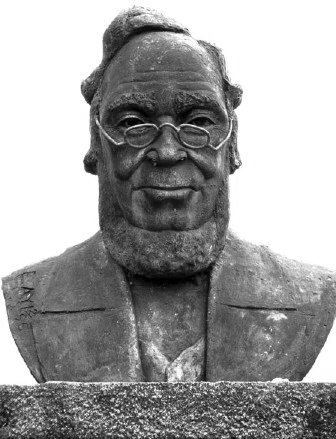

A bust of Hope Masterton Waddell outside the school he founded in Calabar, nigeria

REV HOPE MASTERTON WADDELL was an Irish-born missionary who served in Jamaica and then Calabar, Nigeria. He arrived in the Caribbean when the struggle against slavery was reaching crisis point. Sam Sharpe, an enslaved man who was a literate and well respected deacon in charge of a missionary chapel in Montego Bay, was agitating for complete emancipation. At Christmas 1831, Sharpe – using the network of Native Baptist churches – organised a rebellion in the mistaken belief that freedom had already been granted by the British Parliament but was being withheld by the planters. His plan was to withhold labour at a time when the cane needed to be cut, but events quickly spiralled out of control, as Masterton Waddell recounts.

“Tuesday (Christmas Day having fallen on the Sabbath) was appointed for our customary Christmas Church meeting; but religious feelings were for the time in abeyance. At Dun’s Hole (present day Dunn’s River Falls) I was again disappointed. Very few people attended; and only one, my assistant elder from the Spring. All was alarm. The negroes there, it was said, had broken into the overseer’s house, and taken away guns and pistols. I hastened thither to seek them, but found only the house-women. They were terrified, and said that the slaves were ready to cut the head off any person that spoke a word in favour of white people. In the negro-houses only the aged and infirm could be seen. Others were watching me and hiding. At length a few were intercepted through whom I sent word to all, that the possession of these arms would endanger the lives of all found with them, and that they must be immediately restored to their place. To relieve their fears of discovery, I proposed that they should be deposited during the night at a certain place, and that the next morning I would come, or failing me, my elder, and would gather and replace them in the “busha-house” and make all fast again, without asking any questions. Happily my words were repeated and regarded, and the next day the dangerous weapons were restored, and nothing was heard again of the matter.

It was long past my usual time when I got back to Cornwall, and there I found confusion and dismay. The congregation which had assembled was dispersing in affright, and would not return at my call. The only answer or explanation that could be got was – “Palmyra on fire”. It was not an ordinary estate fire they spoke of, which neighbouring estates’ people would hasten to put out. Were it even so, it need have caused us no alarm, there being a range of wooded hills between it and Cornwall. It was the preconcerted signal for our part of the country that the struggle for freedom had begun; and the lurid smoke rose high over the hills into the clear air. It was the response to “Kensington on fire,” another sugar estate high up in the mountains towards the interior. Both were visible to each other, and over a great stretch of intermediate country, richly cultivated, and thickly studded with sugar plantations. The one hoisted the flaming flag of liberty, and the other saluted it, calling on all between and around to follow their example. And it was followed. These were grand beacon-fires, frightful conflagrations, visible far and wide, caused by the burning of the great “trash-houses” with their enormous piles of dry crushed canes, stored up from last year’s crop, to supply the furnaces for boiling next year’s sugar. No wonder that even quiet, well-disposed slaves were greatly agitated, when they saw the banner of a great gathering and great conflict floating up to heaven – a conflict in which they and their children would be deeply involved – as they were deeply interested in its issues of early freedom or prolonged slavery.

When alone that evening, we sat pondering, and saying one to another, “What will the negroes next do? What should we do?” Just then Roderick of Barrett Hall made his appearance and claimed his Christmas box. He was a New Providence man, a blacksmith by trade, and mulatto by colour. He had come from Montego Bay, excited by drink and what he had learned there, and he threw out mysterious hints of what we should soon see. Displeased with his speech, I discouraged it, and advised him to go home quickly and quietly. He wanted his “Christmas” first he said, a glass of wine or porter to drink my health. But he had got too much of that already, and I urged him to go home and keep quiet, lest he should get into trouble. That was no time, I told him, for a man to make a fool of himself, when the country was on the eve of rebellion. “Well, minister,” he replied sharply, “every fool has his own sense;” and he went away offended. Poor man, his sense was insufficient for such a time. When I next saw him he was in irons, weeping bitterly, under an armed guard, and condemned to die, not for crime, but for folly; for folly sometimes looks so like crime that it meets the same doom.

Scarcely had night closed in, when the sky towards the interior was illuminated by unwonted glares. Our view in that direction was bounded by the Palmyra Hills, but we could not be long ignorant of the cause of these frightful appearances; and as the fires rose here and there in rapid succession, reflected from the glowing heavens, we could guess from their direction, and the character of master and slaves, what estates were being consumed. Soon the reflections were in clusters, then the sky became a sheet of flame, as if the whole country had become a vast furnace. I dreaded lest the wild spirit of incendiarism should invade our seaside district; and my eyes ever turned towards the Spring where so bad a spirit had already been displayed. But happily the night wore on, and midnight was passed, without a torch being seen in our direction. Then the fires began to die out, and new ones no longer appeared, and we could venture to lie down and rest a little before morning. That was a terrible vengeance which the patient drudges had at length taken on those sugar estates, the causes and scenes of their life-long toils and degradation, tears and blood. But, be it remembered that, amid the wild excitement of the night, not one freeman’s life was taken, not one freewoman molested by the insurgent slaves.

Rev Hope Masterton Waddell (14 November 1804 – 18 April 1895). From Twenty-Nine Years in the West Indies and Central Africa