07 June 1692

The rise and fall of Port Royal “the wickedest city in the world”

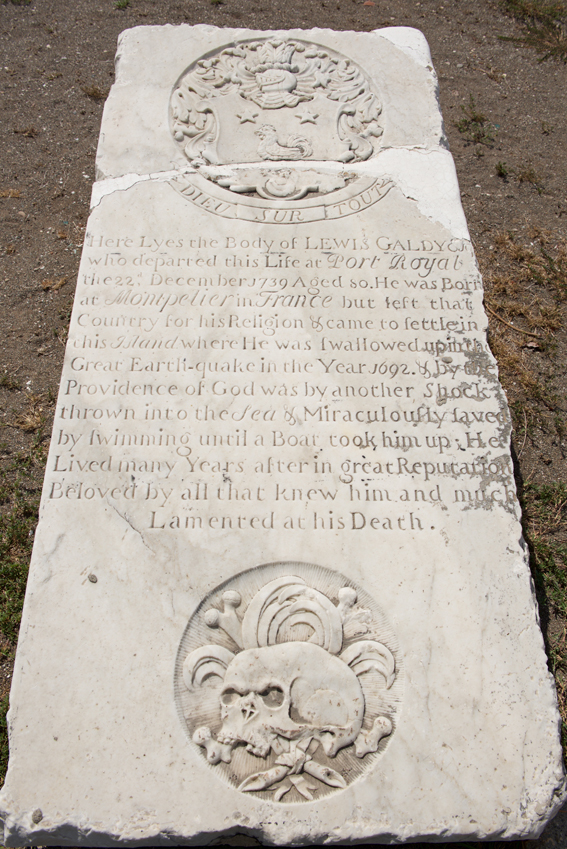

The gravestone of Lewis Galdy in the churchyard at Port Royal. The inscription reveals that he was born in Montpelier in France and was swallowed up by the Great Earthquake of 1692 and then by the providence of God, thrown by another shock into the sea and miraculously saved. Photo ©Derek Bishton

FOLLOWING the capture of Jamaica from the Spanish in May, 1655, the English forces left to guard the island began building a fort to control access to Kingston harbour and a small community, known as The Point, grew up around it. After the overthrow of Cromwell and the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, the Point was renamed Port Royal and almost overnight it became the haven of choice for pirates and privateers from all over the world when Governor Doyley invited the Brethren of the Coast – a syndicate of pirates made famous in recent times by the Pirates of the Caribbean movies – to make it their home port.

Doyley’s embrace of the pirates was seen as the most expedient way of fortifying the island against the threat of any further Spanish attentions. The Brethren was made up of descendants of cattle-hunting boucaniers (later anglicized to buccaneers) who had turned to piracy after being thrown out of Hispaniola by the Spanish. They formed alliances with other privateers such as Sir Henry Morgan, probably the most notorious pirate of the age, who later became Governor of Port Royal and an admiral in the Royal Navy – such was the career path of the times.

Thereafter Port Royal grew faster than any other town founded by the English in the New World. In tandem with English merchants, the boucaniers ran a classic sting operation. They concentrated their attacks on incoming Spanish shipping, which disrupted supplies to Spanish settlements leaving them critically short of essential imported goods.

Then, the Port Royal merchants would sponsor trading missions to the settlements, often selling them items that had been seized from their own ships. Finally, as the Spanish fleets made their way back to Spain laden with gold and other precious cargo, they were again subjected to continuous attacks from the Brethren. This morally dubious and lawless spirit of enterprise soon turned Port Royal into the bawdy capital of the world. In its glory days in the last quarter of the 17th century, hundreds of ships docked there every year, and thousands of sailors with money to burn poured off the ships and into the arms of the prostitutes who frequented the scores of taverns and drinking dens that lined the seafront.

Although Port Royal was designed to serve as a defensive fortification, guarding the entrance to the harbour, it assumed much greater importance. As a result of its location within a well-protected harbour, its flat topography, and deep water close to shore, large ships could easily be serviced, loaded, and unloaded. Ships’ captains, merchants, and craftsmen established themselves in Port Royal to take advantage of the trading and outfitting opportunities.

As Jamaica’s economy grew and changed between 1655 and 1692, Port Royal became the most economically important English port in the Americas.

But Port Royal was always living on borrowed time. It had been built on a sandbank and on June 7, 1692 a powerful earthquake swallowed up the taverns, brothels and other attractions in a geological phenomenon called liquefaction, a process whereby severe earth tremors turn loose, water-filled sandy soil into a sludge. Port Royal literally flowed out into Kingston harbour. Upwards of a third of the town’s 6,500 inhabitants perished and many ships were lost in the tsunami and a hurricane that followed the quake.

There was no shortage of religious commentary on this supposed judgement on “the wickedest city in the world”. London journalist Ned Ward declared it was, “The Dunghill of the Universe, the Refuse of the whole Creation . . . The Nursery of Heavens Judgements . . . The Receptacle of Vagabonds, the Sanctuary of Bankrupts, the Close-stool for the Purges of our Prisons, as Hot as Hell, and as wicked as the Devil.” (1)

A graphic description of the earthquake and its aftermath is found in W. J. Gardner’s History of Jamaica (2). “At twenty minutes to twelve o’clock a noise not unlike thunder was heard in the hills of St Andrews . . . Not only did the earth tremble, and in some parts open beneath the feet of the terror-stricken inhabitants, but the horrors of the event were intensified by the mysterious awful sounds that one moment appeared to be in the air, and then in the ground. . . The wharfs loaded with merchandise, and most of the fortifications, together with all the streets near the shore, sunk into the harbour and were completely overwhelmed . . . In places the earth opened, swallowing up many hapless creatures.”

Gardner recounts the story of one fortunate survivor called Lewis Galdy, who was swallowed by the earthquake, then cast out into the sea by another tremor, where he escaped by swimming to a boat. His gravestone, which now rests in the churchyard at Port Royal, reveals that he lived to the ripe old age of 80, dying in 1739, 47 years after the earthquake.

Aside from devastating Port Royal, the earthquake and hurricane of 1692 had a decisive impact on the way the fledgling colony was to develop. A further two more destructive storms, in 1712 and 1714, crushed the aspirations of the community of small landowners who had settled following Cromwell’s land grants and this, along with the enormous wealth generated by the merchants during the glory years of Port Royal facilitated the transition to monopoly control and large-scale, single crop economic development – sugar plantations. This effectively shaped the island’s destiny, the impact of which is still evident today.

(1) From A trip to the West Indies, Ned Ward, London, 1698

(2) History of Jamaica, W J Gardner, London 1876