23-25 July 1900

The first Pan African Conference

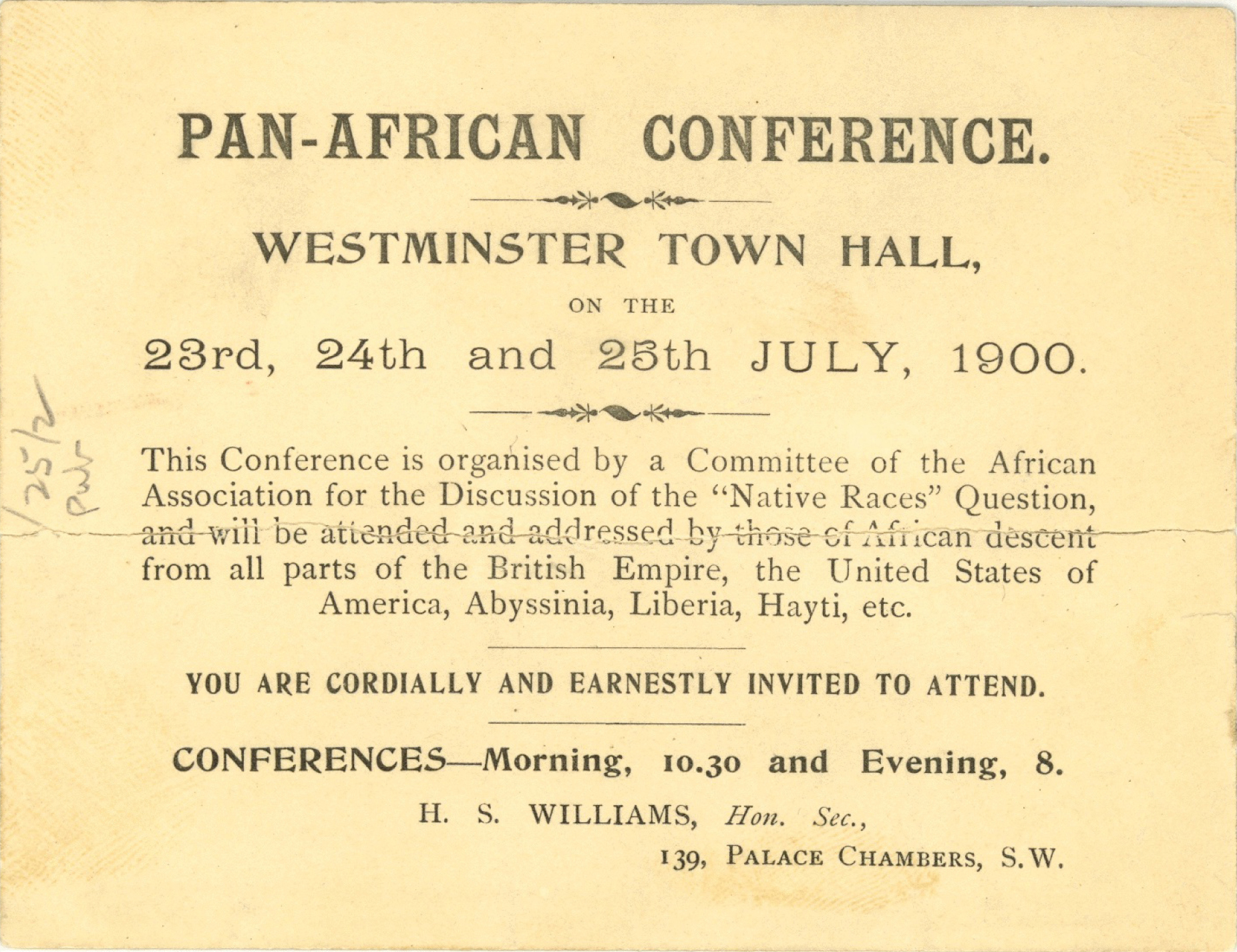

Invitation to the Pan-African Conference, July 1900. By kind permission of the Department of Special Collections and University Archives, W. E. B. Du Bois Library, University of Massachusetts Amherst

PAN-AFRICANIST ideals emerged in the late nineteenth century in response to European colonisation and exploitation of the African continent. Pan-Africanist philosophy held that slavery and colonialism depended on and encouraged negative, unfounded categorisations of the race, culture, and values of African people. These destructive beliefs in turn gave birth to intensified forms of racism, the likes of which Pan-Africanism sought to eliminate. The first conference was held in London in Westminster Town Hall (now Caxton Hall) and was attended by 37 delegates and 10 observers.

As a broader political concept, Pan-Africanism’s roots lie in the collective experiences of African descendants in the New World. Africa assumed greater significance for some blacks in the New World for two primary reasons. First, the increasing futility of their campaign for racial equality in the United States led some African Americans to demand voluntary repatriation to Africa. Next, for the first time the term Africans, which had often been used by racists as a derogatory description, became a source of pride for early black nationalists. Hence, through the conscious elevation of their African identity black activists in America and the rest of the world began to reclaim the rights previously denied them by Western societies.

In 1897, Henry Sylvester-Williams, a West Indian Barrister, formed the African Association in London to encourage Pan-African unity; especially throughout the British colonies. Sylvester-Williams, who had links with West African dignitaries, believed that Africans and those of African descent living in the Diaspora needed a forum to address their common problems. In 1900, he organised the first Pan-African meeting in collaboration with several black leaders representing various countries of the African Diaspora. For the first time, opponents of colonialism and racism gathered for an international meeting. The conference attracted global attention, placing the word “Pan-African” in the lexicon of international affairs and making it part of the standard vocabulary of black intellectuals.

The initial meeting featured thirty seven delegates, mainly from England and the West Indies, but attracted only a few Africans and African Americans. Among them was black America’s leading intellectual, W.E.B. Du Bois, who was to become the torchbearer of subsequent Pan-African conferences, or congresses as they later came to be called.

Conference participants read papers on a variety of topics, including the social, political, and economic conditions of blacks in the Diaspora; the importance of independent nations governed by people of African descent, such as Ethiopia, Haiti, and Liberia; the legacy of slavery and European imperialism; the role of Africa in world history; and the impact of Christianity on the African continent.

Perhaps of even greater significance was the formation of two committees. One group, chaired by Du Bois, drafted an address “To the Nations of the World,” demanding moderate reforms for colonial Africa. (1)

The address implored the United States and the imperial European nations to “acknowledge and protect the rights of people of African descent” and to respect the integrity and independence of “the free Negro States of Abyssinia, Liberia, Haiti, etc.” The address, signed by committee chairman DuBois as well as its president Bishop Alexander Walters, its vice president Henry B. Brown, and its general secretary Sylvester-Williams, was published and sent to Queen Victoria of England. The second committee planned for the formation of a permanent Pan-African association in London with branches overseas. Despite these ambitious plans, the appeals of conference participants made little or no impression on the European imperial powers who controlled the political and economic destiny of Africa.

(1) The document contained the phrase “The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the colour-line”, which Du Bois would use three years later in the Forethought of his book The Souls of Black Folk.

This is an excerpt from an article by Professor Saheed Adejumobi which first appeared on the Black Past website (https://blackpast.org/perspectives/pan-african-congresses-1900-1945). Many thanks to Professor Adejumobi for his kind permission to reproduce it here.